January 21, 2026

Inside Mixedbread: How We Built Multimodal Late-Interaction at Billion Scale

11 min read

January 21, 2026

Mixedbread Team

Most semantic search issues don't show up as obvious failures. They show up as results that look reasonable, read well, and are still wrong. In our experience, this is a structural limitation of single-vector retrieval on dense and unfamiliar inputs: the representation collapses detail, and the retriever confidently returns "close enough" content that doesn't actually answer the query.

Building a reliable retriever is also harder than it looks. You're stitching together parsing, chunking, embedding, metadata extraction, and ANN search, and each stage introduces its own brittleness. When quality drops, it's rarely clear whether the problem is upstream ingestion, representation, indexing, or scoring.

We built a multimodal late-interaction retrieval system to make those failure modes rarer and easier to reason about. The system uses multi-vector representations across text, images, audio, and video, and it's deployed at billion-document scale: 1B+ documents indexed, 500+ QPS per store, and ~50ms search latency end-to-end. The rest of this post walks through the three pieces we had to build and jointly tune to get there: ingestion, encoding, and retrieval.

Multimodal Ingestion

For the vast majority of our embedding purposes, our goal is to create a true end-to-end representation pipeline, where we retrieve information from exactly where it lives in the embedding space, surrounded by all the valuable context.

This means that audio files are first pre-processed to maximize quality before being passed to the model, which dynamically splits it into meaningful units on its own. For textual inputs, we have a series of pre-processing steps which ensures the data is broken down into manageable blocks ("chunks") while maintaining all necessary context. Code is treated as its own separate input, with the AST parsed to determine logical cutoff points. For images, the model natively processes pixels.

As for document formats, like PDFs and PowerPoint, every single page is individually exported to screenshots of the pages, ensuring that all visual and layout information, such as tables and graphs, are preserved and represented as individual semantic units, with context such as headings preserved across pages.

Unlike most other systems where the model's training data is largely decoupled from expected real-world inputs, our model is trained specifically on the output of these pre-processing steps. This ensures that it is fully optimized to retrieve documents exactly as they will be in production and yield more accurate search results.

Even though our model can process the format of every type of document natively, that does not mean that downstream applications can use this information as effectively. Up until recently, the vast majority of the world's applications were built with text as the first-class, and often only, citizen. As such, parallel to preparing inputs for representation, our ingestion pipeline also runs a full document analysis step to extract texts from the input. As a result, audio and video files are transcribed, and PDFs are converted into fully human and LLM-readable markdown format using our custom OCR pipeline.

Multimodal Late-Interaction Encoding

"Traditional" semantic search relies on a simple, single-vector approach: an input is provided to a model, which then outputs a single vector representing the entire document. Single-vector search has many advantages. It is fast and exceedingly simple to implement. However, it is also extremely lossy: while a single vector can capture paraphrases and general meaning well, it dilutes details and precise intent, and it struggles with information-dense documents, such as technical, legal documents and academic papers, especially in multimodal settings.

ColBERT pioneers a multi-vector approach, which replaced traditional single-vector representations with individual, lower-dimension token-level representations. These token-level representations preserve fine-grained information in both the query and the documents. In practice, it yields more accurate search results in out-of-distribution settings, where real-world papers, slideshows or long-context texts may look fundamentally different from the training data. For example, our 17 million parameter open-source ColBERT outperforms 8 billion parameter embedding models on the LongEmbed benchmark, which measures the ability of embedding models to perform long-context retrieval tasks.

In our experiments, we found that not only can multi-vector representations be compressed while continuing to capture fine-grained meaning, they also significantly outperform single-vector alternatives on image, video and audio search.

| Benchmark (NDCG@10) | Best Single Vector Model | mxbai-wholembed-v3 |

|---|---|---|

| OHR-V2 | 86.47 (Qwen 3 VL 8B) | 91.26 |

| Miracl-Vision | 59.79 (Qwen 3 VL 8B) | 66.02 |

| Vidore 3 | 64.81 (Qwen 3 VL 8B) | 67.9 |

mxbai-wholembed-v3 is currently in internal evaluation and will be available soon. We are publishing an in-depth release about the model benchmark soon. The benchmarks shown are challenging multimodal evaluations. As of Jan. 2026, Qwen 3 VL 8B is the latest release and achieves SOTA performance across multimodal and text only benchmarks.

mxbai-wholembed: A Unified Multimodal Encoder

Leveraging our team's previous frontier work on both embedding models and ModernBERT, among other things, we trained mxbai-wholembed, our unified multimodal late-interaction encoder.

This unified model produces semantic unit-level vector representations, across text, image, audio, and video inputs, in a shared latent space, accurately capturing semantic relationships across modalities. Many previous state-of-the-art systems opted for modality-specific approaches, which introduced complexity by requiring modality-specific handling and yielded performance tradeoffs orthogonal to scaling laws. By sharing one latent space, we unlock "any-to-any" search and streamline architectural constraints by removing the need for any such modality-specific routing and storing. Throughout our experiments, we found that the bitter lesson of the effectiveness of gradient descent continues to hold true. Rather than competing, we observed that properly orchestrated multimodal training in a single, shared embedding space resulted in a lifting effect: improving the quality of image retrieval, for example, also improved performance for both audio and text retrieval.

Scaling Laws

Our experiments showed that, despite the huge attention given to the BERT-scale model, scaling works for retrieval. This has also been independently demonstrated in the best paper award winner at SIGIR, the premier Information Retrieval conference.

Unlike the situation around LLMs, retrieval scaling laws are largely underexplored, poorly understood, and rarely used for downstream production settings. In spite of this, we found that larger scale models consistently allow for better cross-modality alignment and handling of complex information, such as composed queries, at the expense of significant efficiency constraints.

After careful experimentation, we have settled on an infrastructure that, combined with a custom-designed inference engine, strikes the right balance at the Pareto frontier of latency and retrieval performance.

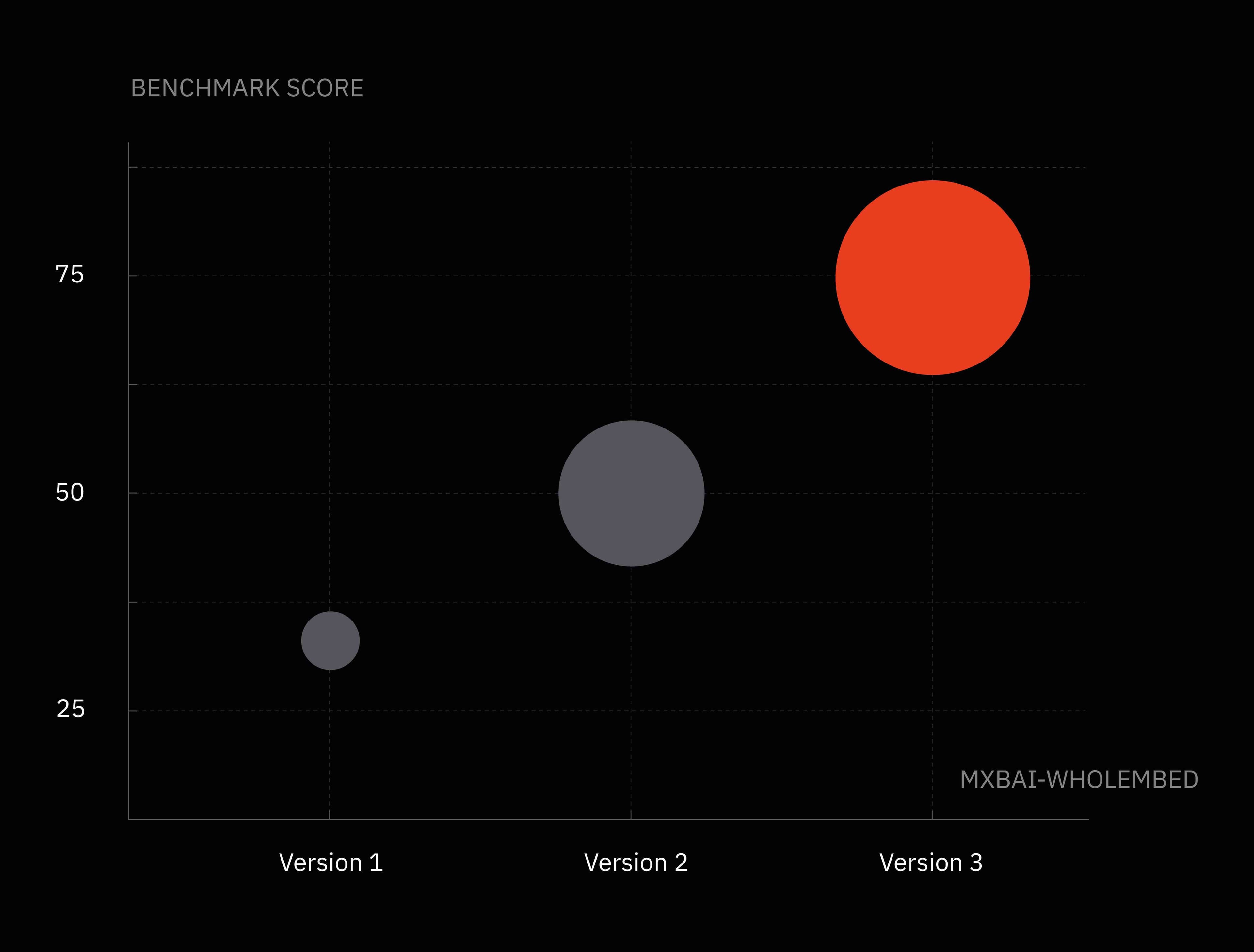

This optimised stack has led to considerable scale increases: mxbai-wholembed has over 20 times the parameter count of our original multimodal model, and three times that of our previous one. With every generation, we saw considerable improvements in our models, especially in real-world edge cases poorly captured by standardized benchmarking.

mxbai-wholembed-v3 has 20 times the number of parameters of v1. This scale increase leads to considerable performance improvements.

Dynamic vector allocation

mxbai-wholembed estimates the information density of a given input and decides the necessary number of vectors to represent it accordingly. For example, a simple cat image may output a few vectors, whereas a complex slide deck may generate thousands of vectors. This dynamic allocation of representation capacity prevents semantic collapse on dense content often experienced by single vector representations. The optimal size of allocation is determined based on large-scale internal experiments to allow mxbai-wholembed to capture fine-grained information while keeping storage requirements low.

Billion-scale Late-Interaction Retrieval

While late-interaction makes retrieval more accurate for real-world uses, it also creates a scale challenge. A single document can produce hundreds or thousands of vectors; a single collection of documents can then contain millions of vectors to search across.

The Scale Challenge

Single-vector search efficiency is greatly helped by relying on very simple operations at the hardware-level, making storage and search straightforward. Additionally, it benefits from decades of approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) index research: algorithms like HNSW, SPFresh, and DiskANN bring search to near-constant time.

This simplicity is why many semantic search platforms heavily favor single vector offerings: they remove considerable complexity and are extremely cheap to scale. However, the tradeoffs to retrieval quality are significant and theoretically demonstrated to be impossible to overcome with our current understanding (Weller).

Conversely, late interaction approaches have been demonstrated to greatly alleviate these tradeoffs, but break many of the simplicity assumptions that power large-scale single vector search. Specifically, they introduce three compounding challenges:

- Limited indexing support for multi-vectors: The vast majority of current ANN indexing methods are not built for multi-vectors. With hundreds of vectors per document, scanning becomes prohibitively expensive and searches can take seconds instead of milliseconds.

- Scoring is expensive. A single-vector document requires a single inner product calculation: scoring across a million documents is ~ 1 million operations. With multi-vector methods, a document with 256 vectors scored against a 16-vector query requires 256 x 16 = 4,096 (inner product followed by score aggregation): scoring a million documents now requires 4 billion operations.

- Storage scales with vectors. More vectors per document means more storage, more memory and more I/O pressure.

silo: An S3-Native Retrieval Engine

silo is a custom multi-vector retrieval engine designed to support late-interaction at billions-of-documents and trillions-of-vectors scale and maintain the flexibility of common ANN indexes. Three crucial optimizations bring the search latency under 50ms.

Two-Stage Retrieval

silo performs two-stage retrieval to make the search space tractable. Stage 1 pre-filters the search space using approximate searches and metadata filtering, and reduces it from billions of documents to a few thousand candidates. Stage 2 scores the candidate documents using MaxSim.

silo maintains and updates the document indexes at write time when documents are ingested, with no performance cost during retrieval. Consequently, there is no index building in preprocessing or latency hits on CRUD operations common in ColBERT-like methods.

Accelerated Scoring

A few months ago, we wrote and released maxsim-cpu, a high-performance Rust implementation of MaxSim on CPU. You can read more about it in our blog post.

In production today, we went a step further and run a version of maxsim-cpu further optimized with custom kernels targeting the specific hardware of our inference pipeline, along with aggressive vector quantization to speed up scoring.

As a result, scoring a thousand candidate documents using MaxSim takes under 3 milliseconds and a single CPU processor is sufficient to handle thousands of QPS.

Object Storage with NVMe Caching

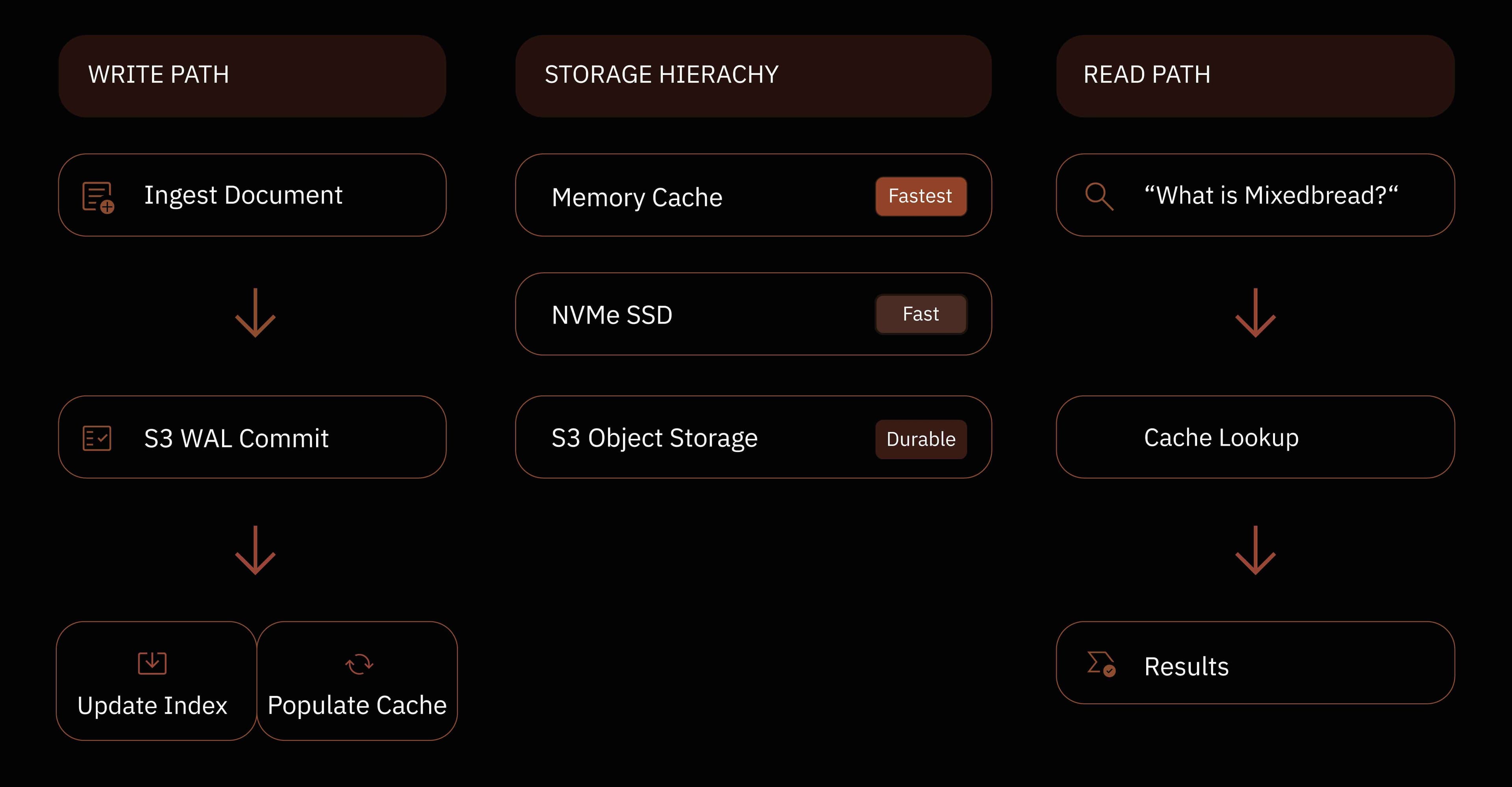

All vectors are stored in low-cost, replicated S3 object storage for scalability, durability and as the source-of-truth. Actively accessed vectors are loaded at query time into NVMe SSDs and cached in memory for computation.

On the write path, both vectors and metadata are persisted to a write-ahead log (WAL) in S3, and their index and cache are populated synchronously.

Guarantees:

- Writes acknowledged only after S3 WAL commit (durability)

- Data never lost even if compute nodes fail (fault tolerance)

- Hot stores served from cache (memory-like latency)

- Cold stores hydrated on-demand, cached for subsequent queries

This allows us to serve billions of vectors per tenant while keeping retrieval speed in milliseconds.

Performance

| Stage | Latency | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Query encoding | 10-20ms | Custom inference engine |

| Stage 1: Pruning | <10ms | Billions → ~1000 candidates |

| Stage 2: Scoring | 5-10ms | Custom kernels |

| Result assembly | ~10ms | Metadata, snippets |

| Total | ~50ms |

Latency measured at P50 on a production system with hot cache. QPS per store means each store (search index) can sustain over 500 QPS.

Why it matters

Retrieval has always been, and continues to be the natural interface to information. Traditionally, it was how you found useful websites and relevant snippets. Nowadays, it's how agents find exactly the pieces of context they need to answer a user's query. But retrieval has been stagnant for too long, and it has become clear that the once-omnipresent single-vector text representation is not meeting the needs of this new generation of users. Agents need the model to be able to understand long, reasoning-intensive queries. They need the ability to retrieve documents where they live, be they text, images, pdfs or even videos.

We're building Mixedbread to close the gap between Search that is possible today and what the users of tomorrow will demand. If that sounds like a problem you'd want to work on, we're hiring.

11 min read

January 21, 2026

Mixedbread Team